HUMBLE_HUMBOLDT [@]

Governing the apocalypse

How jihadists in the Sahel became environmental managers

By Humble_Humboldt.

Acknowledgement: For the writing of this article, I owe a debt of gratitude to fellow substacker qua Third Worldist Rob Ashlar, whose own recent post about Sahelian jihadism served as a critical reference for this timely yet woefully under-researched issue.

FOR ALL THE TIME AND MONEY THAT THEY’VE POURED INTO FIGHTING A WAR AGAINST IT, Americans seem to be remarkably ignorant about the geography of global terrorism in the 21st century. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Africa’s Sahel region, where—despite a decade-spanning explosion in violence by and against various jihadist groups, including those with proven links to ISIS and Al-Qaeda—an entirely avoidable media blackout has rendered the phenomenon invisible to the very people whose tax dollars are being used to (supposedly) combat it. The result is a cultural consensus in which concern about terrorism can start and end with the West without ever broaching the one part of the world where it has killed more than five times as many people as 9/11 since 2023 alone.

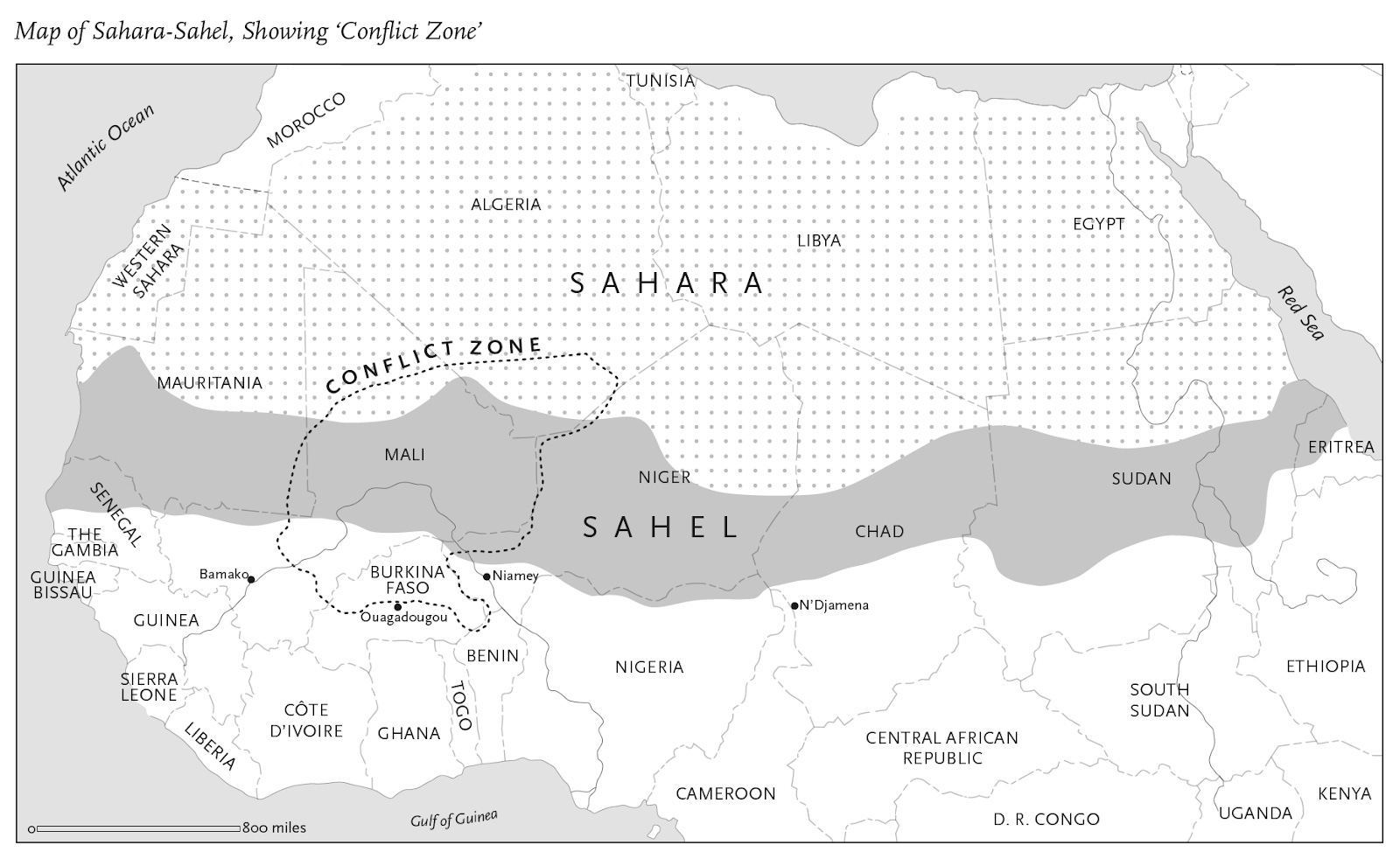

Figure 1: Map of the Sahara-Sahel

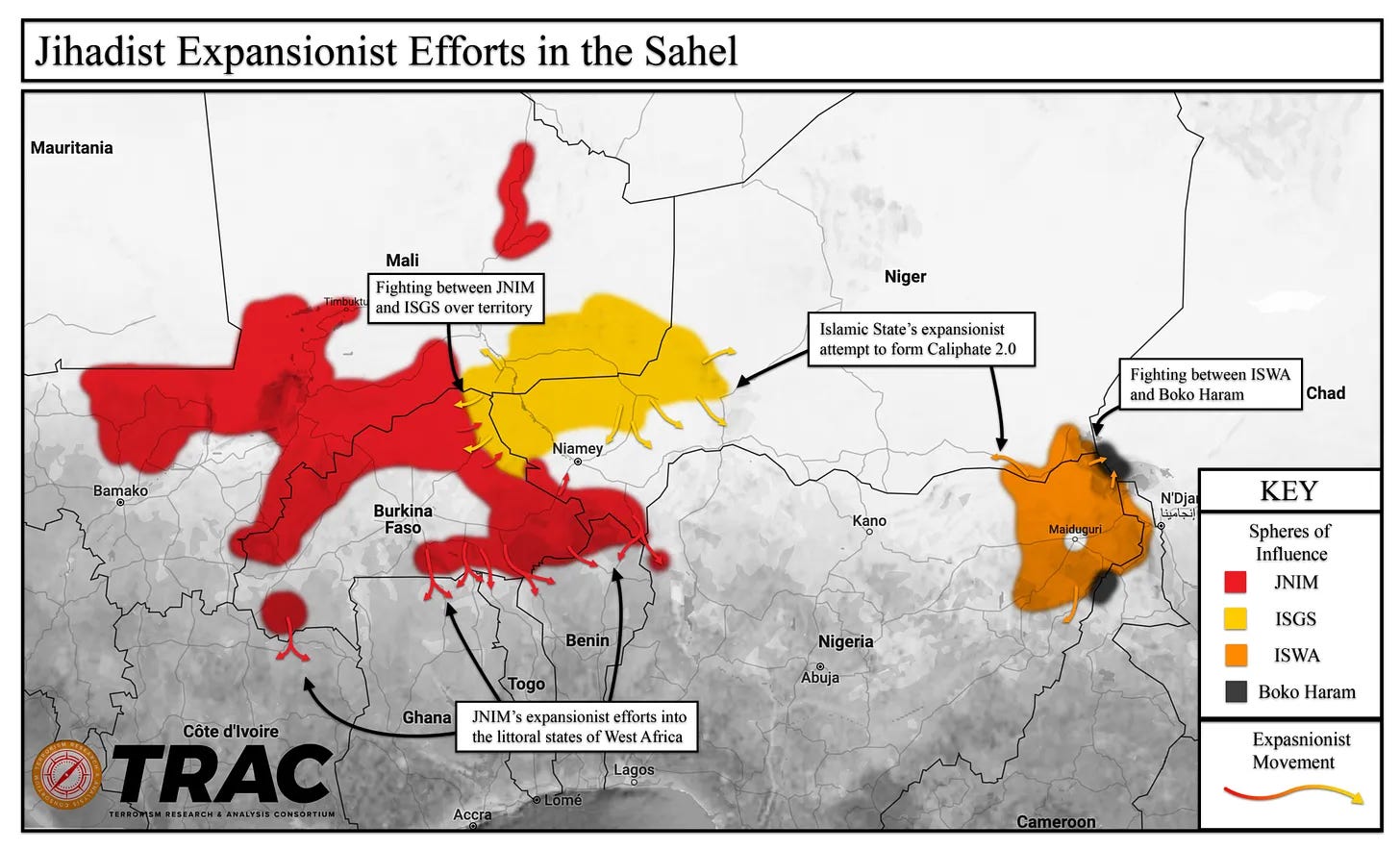

Figure 2: Respective spheres of influence of multiple jihadist groups in the Sahel as of June, 2024

Conversely, wherever sins of omission can be found, sins of commission are rarely in short supply. In the case of the Sahel, the few segments of the Western commentariat which have acknowledged its suffering seem content to depict the matter as a kind of epiphenomenon of the region’s natural history. In particular, such accounts place a high premium on the agro-pastoral livelihoods which have dominated large swathes of the Sahel for centuries; given their mounting unsustainability in the face of a dwindling (not to mention increasingly climate-inflected) resource base, so the argument goes, it’s no wonder that this pair of vocations has been so effective at stoking the flames of regional conflict. Indeed, considering their longstanding refusal to bow before the dictates of global capitalist sensibility, the real question is why they hadn’t begun to do so even sooner.

As it happens, this isn’t the first time the Euro-American press has attempted to launder African death as a geologic force. Half a century ago, amid the demographic convulsions of the catastrophic 1972-75 Sahel famine, a similar flurry of racist tropes conspired to naturalize a crisis which researchers both then and since have found to be distinctly social in origin (if not its proximate cause). All the same, one can’t help but discern something particularly craven about the latest epistemic crusade against the people of the Sahel: long ago deprived of the right to stable nutrition, now they can’t even enjoy a life free from nonstop civil war without the Earth intervening to thwart them! Against this manufactured teleology, I propose to conduct in these pages a frank reconnaissance of environmental warfare in the Sahel. What relation (if any) is there to be found between West African jihadism and the natural world? Why might such a relation exist in the first place? And—perhaps most explosively—whom ought we to point the finger of blame toward if one exists?

Conventional accounts of jihadism in the Sahel begin sooner than one might expect. In 2011, on the heels of the then-recently initiated Arab Spring, an ascendant Libyan protest movement mobilized to unseat the erstwhile Gaddafi regime from power. Lacking the manpower or arms to bring this end to fruition themselves, this vocal minority would soon receive an unexpected helping hand from NATO, which lent generous military and financial support to rebels on the ground fighting against Gaddafi’s men. In addition to securing a decisive rebel victory, NATO’s intervention triggered a surge in regional violence and arms proliferation of levels not observed since the Algerian Civil War. This bedlam would subsequently spill over into neighboring Mali, where it provided ample grist for ethnic Tuareg secessionists who had been attempting to overthrow their own ruling government for decades. Working hand in glove with jihadists streaming in from both Libya as well as the then-receding Iraqi insurgency, Tuareg militia orchestrated a coup which landed both groups more or less total control over Mali’s northeast—only for the former to then betray the latter and impose its own absolutist rendition of Quranic law, or shari’a, on the local population. Though this outcome would later be reversed by a French military intervention, the damage was done; jihadists had obtained a new arena in which to make good on their millenarian vows, and it was not one they would give up easily.

Where the role of nature enters into play here may not be immediately apparent. According to the received wisdom, Sahel states’ vulnerability to jihadism tends to increase in direct proportion to the numbers of one ethnic group: the Fulani. Predominantly pastoral in vocation, this unhappy minority admittedly has something of a history with waging holy wars. During the twilight of precolonial rule in the Sahel, Fulani armies across the region mobilized to erect a series of religious states governed by strict adherence to shari’a. The crowning achievement of their efforts was the 19th-century Sokoto Caliphate, whose regional cachet outshone those of all its rivals before it was dismembered by Britain, France, and Germany a century after its founding. Second to it was the sprawling Macina Empire, a polity of such renown that its history is even cited by a regional branch of ISIS to justify ongoing attacks against the Malian state today!

Yet there’s more to the Fulani-jihadism nexus than simple nostalgia. As many an analyst has noted, this ethnic group’s fluid relationship to the land of the Sahel has rendered the latter a prime battleground for ecological class conflict. More precisely, by mining the region’s shrinking endowments of the resources which make their livelihoods viable—land and water for pasture, timber for fuel, etc—Fulani herders have occasioned numerous clashes with farmers operating in or near the areas they wish to (temporarily) claim for themselves. In most cases these farmers can reliably count on the state and/or some customary body acting on its behalf to rule in their favor,1 an asymmetry which substantially inflates the allure of jihadists—and, in particular, the capacity of the arms they carry to alter the balance of forces—to disempowered herders. This dynamic in turn begets a vicious positive feedback, with Sahel states citing Fulani participation in jihadist activity to sanction hideous violence against their communities and aggrieved Fulani flocking to the ranks of jihadists as a means of (real or imagined) self-defense in response.

The present abjection of the Fulani can be traced back to two misperceptions, both of which require a certain degree of tunnel vision in order to be sustained. The first one insists that Fulani pastoralism is a constitutively warmaking enterprise; this stereotype, of course, enjoys a geographic scope well beyond the West African Sahel. Given its essentially intractable nature, so the argument goes, the pastoral mode of living can’t not challenge the parameters of the modern nation-state (and, by extension, the latter’s claimed ability to prevent society from collapsing into a Hobbesian war of all against all). Among these parameters, two stand out. For one thing, the mobility which pastoralists rely on for their way of life places them at a certain remove from the “civilizing” procedures of modern statecraft, i.e. identity documentation, taxation, formal education, etc. Said remove in turn exposes them to the corrosive influences of “barbarism,” thus affecting the erosion of that second load-bearing parameter of bourgeois sovereignty: property rights. For the regimes of the Sahel, this coupling is thought to be the foremost contributor to Fulani militancy, a suspicion which has likely grown in weight since foreign, land-hungry monocropping operations began to visit the region at increasing rates during the 1970s:

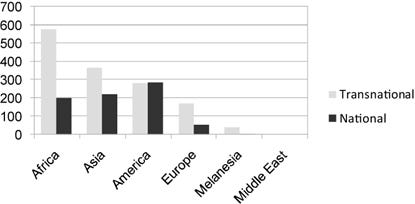

Figure 3: Large-scale land grabs (number of deals reported) by world region, as cited. Since the French conquest, competition with Western agribusiness, ranching, and mining companies has greatly increased the scarcity of available pasture for Sahel pastoralists.

Beyond the economic, moreover, Fulani herders are routinely accused of being environmental vandals. As with so much else wrong with the world, the origins of this noxious canard can be attributed to the French. During the early-20th century, colonial scientists maligned pastoralists as wanton predators of the Sahel’s natural wealth, particularly its forests. The logical corollary to this predation was the imposition of extreme police measures to save African ecosystems from Africans themselves. To quote the opinion of one influential botanist, Auguste Chevalier:

The remedies to be applied are the same everywhere: (1): Bush fires must be prohibited wherever deforestation is a danger, (2): It is also necessary to fix the nomadic forest populations and assign to each village a territory from which it cannot deviate, [and] (3): It is necessary to delimit now and register certain forests which will have to remain permanent in the future, and to entrust their conservation and maintenance to a forestry service with sufficient means of action [...].

In the event, Chevalier’s wishes would crystallize in the 1935 forest décret, whose Lockean conception of “productive” land-use all but eliminated space for pastoralists’ (decidedly non-capitalizable) engagements with Sahelian forests, e.g. woodcutting, grazing animals, picking nuts and fruits. This resource apartheid was further reinforced by an earlier distinction which colonial lawmakers had enacted between “citizens” (urban, literate, rights-bearing) on the one hand and “subjects” (rural, poor, usufructuary) on the other. The upshot was a novel, intentionally unnavigable system of permits, fines, and levies which converted what had once been a common resource into a blackbox to be partitioned and gatekept. This militarized subtext to the décret was made evident by the parallel birth of the French West African Forest Service, which drew its ranks not primarily from colonial foresters and hydrologists, but rather the police and armed forces.

Needless to say, the depredations of West African forestry agents were not discontinued with independence; to the contrary, they were usually escalated. In postcolonial Mali, for example, a series of revisions to the 1935 décret—each justified on the basis of combating desertification—culminated in a 1986 ban on cutting trees or collecting drywood without the state’s blessing. This resulted in widespread rent-seeking by forestry agents, many of whom were wont to impose towering fines on people even when the wood they collected originated from dead or privately owned trees. Such opportunism was more recently mirrored by one forestry dispute implicating a shepherd in Burkina Faso, where—despite cutting a single branch in an area reserved specifically for pastoralists—the man in question was fined an amount equal to 90% of the value of his entire flock of oxen (later reduced to 20% upon appeal).

But the troubles of the Fulani don’t end there. Also largely in continuance of their imperial forebear, Sahel states have aggressively promoted the sedentarization of herders as a bastardized means of “conflict resolution.” Their principal tool for accomplishing this is the creation of state-designated corridors for pastoralists which—though perhaps benign in theory—have the effect of confining the latter to spaces that render their traditional practices impossible. Thus although the Burkinabe government is set to increase the number of pastoral territories under its watch to 120 by next year, it’s only doing so with the express aim of using these territories as hubs for intensive, American-style cattle ranching. Such ventures in turn warp relations between herders, with those among them who have jumped on the bandwagon of settlement increasingly coming to exert dominance over those who haven’t. This further compounds the latter group’s vulnerability to many of the aforementioned customary and state actors, resulting in such manifold ills as extortion, racketeering, bribery, and outright theft.

As noted earlier, Fulani receptiveness to jihadism has much to do with the failure—indeed, the militant refusal—of Sahel states to treat them as equal partners in the governance of regional land-use. In addition to souring their faith in the ability of their rulers to fairly address the challenges wracking the Sahel today (e.g. insecurity, climate change, grinding poverty), this indifference has also spawned widespread nostalgia for the justice which is thought to have once underwritten farmer-herder relations.2 More than anyone else, it is jihadists who promise to restore this justice, above all by simply reversing the colonial-era enclosures which have driven so many people across the region to the brink:

For the jihadists, attacking forestry agents is therefore also a way of attracting the sympathies of part of the population, and in particular the breeders. “They don't just free up the forests to be able to settle there. They also free them up for all users who were prevented from carrying out activities there by the foresters and who are delighted to be able to return without the risk of being arrested or taxed. This is how they gain supporters. Moreover, this is the message they send when they arrive in an area: ‘You can go back to the forest, it is yours,’” said a local elected official from the eastern region of Burkina Faso…“As soon as they took control of the forest, the activity resumed with renewed vigour,” explained Dahani, a resident of Madjoari, a town in eastern Burkina Faso surrounded by national parks, a few months ago. “Shepherds have arrived from all over the place with their flocks. Poachers have come from Benin. And gold miners have once again searched for gold even though the state had forbidden them to do so” [emphasis added].

To grasp why these interventions “work,” it helps to understand why the policies they’re responding to were never merited in the first place. Returning to the first keystone of anti-Fulani prejudice, it has simply never been the case that peace in the Sahel coexisted alongside exclusively sedentary lifestyles. Indeed, as Matthew Turner makes clear in his recent article on the matter, mobility (in the sense of continuous movement rather than a one-and-done migration from point A to point B) has been a fundamental tenet of life in the Sahel for generations. One reason for this is the region’s pendulum-like climatic fortunes. Being enveloped by the high-pressure zone which gives the Sahara its desert status, this part of the world derives the bulk of its rainfall from seasonal meanders in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), a low-pressure belt spanning the Earth’s diameter where easterly winds from the Northern and Southern hemispheres clash:

Figure 4: Alternate locations of the ITCZ during summer and winter in the Northern hemisphere, respectively.

Over the course of centuries, this fantastic movement of air masses has been coupled by an equally robust movement of people: a veritable human-nature dialectic which has left its imprint on most aspects of the social and material worlds of the Sudano-Sahel. For example, a common feature of subsistence economies in the region is the dependence of local households on remittances from migrants in the (significantly more salubrious) Gulf of Guinea. In addition to strengthening food security up north during times of need, these linkages have equipped otherwise insulated villages with such beloved tokens of modernity as refrigerators, radios, electric generators, chic furniture, and even television! What’s more, the synergies often work both ways. Thus north-south migration in the region has been of such magnitude and duration as to feed the establishment of several migrant enclaves, or “clubs,” across the West African littoral. These clubs serve as a critical buffer for Sahelians on the move, inserting them into networks which can pair them with job opportunities, help safely remit a portion of their earnings back home, or simply grant them a sense of community in an otherwise alien environment.

Far from destabilizing, mobility has thus played an unmatched role in consolidating social order in the Sahel; pastoralists are no exception. Indeed, largely following the north-south migrations of the ITCZ (albeit with a more sensitive eye to elevations in the regional water table), they and their flocks once served as vectors of goodwill between farmers and herders in a region where such goodwill is today all too elusive. The principal mechanism for this harmony was intergroup traffic of the limiting factors to agricultural and pastoral production. Keen to avoid shortages of basic nutrients, farmers across the Sahel would acquire fertility-boosting dung from Fulani herders in exchange for allowing the latter’s cattle to graze their harvested land during the dry season. Known as the contrat de fumure (“fertilization contract”), this relation of mutual benefit went a long way toward aligning the interests of each producer with those of its would-be competitor. Indeed, so powerful was/is the contrat that at least one Burkinabe village has already successfully deployed its logic to defuse enmity between farmers and herders:

Before the development of the perimeter fence at Toèghin, Désiré Nabaloum [farmer] never authorised the incursion of herders into his fields. “After sowing, we were obliged to sleep in our fields so the cattle couldn’t come and destroy everything. We suffered enormous losses,” said the farmer, who still remembers an incident which had sparked a violent conflict between farmers and herders in Toèghin several years ago.

“That day there were injuries,” he recalls. “Rational pasturage is what benefits us all.” “This year, I came here twenty times with my cattle,” affirms herder Moumouni Bandé. He confirms that, “since the establishment of the site, there have been no conflicts between us…Before, Désiré and us herders didn’t address each other in the village. But today, these quarrels aren’t relevant anymore.”3

Figure 5: A pastoralist grazes his cattle in a farmer’s field post-harvest.

In some measure, of course, such accords as the above do stand at odds with the discourse of Western property rights. The reasons for this are both twofold and deeply entwined: occupying an environment where the gifts of nature are highly spatially variable, herders must perforce reject any geometrically fixed division of their entitlements to the land (e.g. the pastoral hamlets in Burkina noted earlier). As economists Daniel Bromley, Jean-Paul Chavas, and Roger Vandenbrink elaborate:

Typically, the tribal organisation of a nomadic property regime enables each economic unit to be continuously mobile since no single permanent trek route would be optimal under environmental uncertainty [emphasis added]. The property regime, then, does not define a fixed territory for its members. On the contrary, the relational aspects of property rights are stressed as pastoral peoples need to continually move around. Movements need to be coordinated with other lineages and tribes, as well as with farming populations. The different itineraries of annual transhumance may be coordinated in advance by an assembly of lineages in order to minimise the risk of interference. Under such property regimes, lineage heads function as stewards of the system, while cattle are private property. The lineages thus form a management group that establishes rights and duties with respect to the use of pastoral resources (access to trek routes, pasture, water and so on).

Though undoubtedly imperfect in their own ways, traditional Fulani mechanisms for adjudicating pastoral mobility (many of which once formed a key element of civic rule in the Sahel) thus hold substantial promise for diminishing the currency of jihadists. In order to fully benefit from them, however, Sahel states must undergo multiple and lasting changes of course. Here I shall only articulate the two which I consider to be the most important. First of all, it is urgently necessary for these states to begin treating the Fulani as partners in the battle against jihadism rather than combatants to be eradicated. This would require unlearning the anti-nomad biases which they’ve inherited from French colonial rule, whether that takes the form of repealing the 1935 décret, elevating the legal status of herders, punishing clientelism by state and nonstate authorities,4 or (ideally) all three. Secondly, and as alluded to earlier, the present vogue for surrendering the land of the Sahel to large-scale, extractivist projects must be pared back significantly. This is due not only to the ruinous effects it has visited on pastoralists, but farmers as well. Indeed, by strategically extending credit to producers of market-friendly cash crops, Sahel states have severely limited access to fertilizer for independent smallholders. This incentivizes the latter to raise their output through extensive (rather than intensive) means, thus pitting them against herders/preventing both groups from making use of the contrat de fumure and other practices like it.

Needless to say, the technical and economic obstacles to making these ideas a reality are considerable. Yet on the political level at least, there is actually cause for blunted optimism. The foremost reason for this is that state legitimacy in the Sahel these days seems to be based largely (if not exclusively) on claims to autochthony: who is promising to both recognize and undo the harm which centuries of foreign domination have administered to our people? We observe this in not only the rhetoric of jihadists, but also that of Sahel states themselves. Thus in one speech recited on behalf of Burkinabe junta chief Ibrahim Traoré, one can find (in addition to condemnations of the U.N. and homosexuality) a considerably more measured reflection on the duties of postcolonial damage control: “While it’s true that the West has raped, violated and robbed Africa, what’s our share of responsibility as African leaders?” Though I cannot avow to answer this question any better than Africans themselves, it would likely serve Sahel states well to consider it in light of the evils which actually defined French colonial rule—and whose legacies can be felt all too strongly today.

1 - An example of this would be Sahel states refusing to enforce the sanctity of pastoralist corridors whenever the latter are encroached upon by farmers.

2 - This is eminently related to the aforementioned invocation of the Macina Empire by certain jihadists.

3 - Author’s translation.

4 - Rob elaborates the sheer weight of this point considerably in their discussion of the harsh stratification which has defined Fulani history (“Fulani society is rigidly hierarchical [...]”).

🔻 2025 Humble_Humboldt. All rights waived for the third world. No rights granted to the imperial core or its collaborators.