HUMBLE_HUMBOLDT [@]

Why Israel bombs Gaza but not the West Bank

By Humble_Humboldt.

Note: Apologies if this work seems less organized/more cluttered compared to my last one. I’d originally intended for it to touch exclusively on the subject matter of its title before I convinced myself that its thesis would be incomplete absent a discussion of those “other” topics which, though I won’t disclose here, will make themselves evident over the course of the essay. Next article will probably be about either housing and/or environmental policy in settler states. Cheers.

Introduction

In his excellent recent speech-turned-essay “The Destruction of Palestine is the Destruction of the Earth,” Andreas Malm articulates the contours of a remarkable yet eminently plausible homology between the two operations which form his argument’s namesake. Taking as his point of departure the historical coincidence between the ascent of fossil capital as a global force and contemporaneous proposals to stake out a Jewish colony in the Levant, Malm sketches a classic longue durée account of Palestine’s martyrdom, one which both acknowledges the latter’s particularities without ever losing sight of its enmeshment with logics of a more global scope. Among his most striking analogies (of which there are many) is the one he draws between the entrenchment of hydrocarbon dependence via capital accumulation and the parallel devalorization of Palestinian life by the settlement enterprise:

It is entirely evident that investment in fossil fuel infrastructure must end and indeed should have ended long ago. Yet we see more pipelines, more rigs, more platforms and terminals and mines planned and built, and the more of them there are, the more difficult it becomes to cut emissions, the more fixed capital is sunk into the ground, the greater the imperative to maintain it and defend it against any transition away from fossil fuels. It is entirely evident that investment in racial colonies, too, must end and indeed should have ended long ago. Still, we see more settlements, ever more settlements planned and built on the West Bank and in Jerusalem, and perhaps soon in Gaza, again [emphasis mine]. And the more Palestinian land is confiscated, the more housing units are erected and reserved for Jews only, the more difficult it becomes to envision a withdrawal to the Green Line, the more immovable the occupation, the greater the interest in defending it against any scheme for a viable Palestinian state.

I would like to focus here (of all things) on Malm’s clause-length speculation regarding the potential resumption of Jewish colonization in Gaza. Concerns that such an outcome would materialize were particularly acute a few months ago, by which point leaders of the Israeli settler movement had organized a caucus meeting advocating exactly this which was attended by several high-profile government officials. The referent of their pleas was, of course, the 8,000-strong community of Jewish settlers which had resided in Gaza before 2005, when they were reluctantly evacuated by Israeli PM Ariel Sharon for fear of unnecessarily inflating his country’s Arab population. Yet upon further reflection, I have since concluded that forecasts of an imminent settler revanchism in Gaza (whether from the horse’s mouth or on the part of Palestinians who justly fear that the territory will revert back to the fate of the West Bank) are largely without merit. What’s more, I sincerely believe that the reasons for why this is are inextricable from Malm’s theoretical conjugation of the climate crisis with the genocide in Gaza. Before I can explain the relevant linkages, however, I would first like to raise another, seemingly unrelated matter:

Why is it that Israel has bombarded Gaza with such unhinged ferocity yet left the West Bank (mostly) untouched?

At first glance the answer to this question may seem deceptively obvious: Hamas attacked Israel. Indeed, not only did they attack—they managed to exact the single highest civilian death toll on the Israeli side of the conflict ever. Given this, it’s small wonder that Israel has chosen to devote the better part of its firepower to containing the Palestinians on its leftmost flank. Or at least it would be, if the latter hadn’t already been the victim of repeated—and vicious—aerial onslaughts well over a decade before October 7. Starting from 2008, we can date at least three major massacres Israeli forces committed in Gaza between then and 2022. Perhaps the most infamous among these—what Israelis euphemistically dubbed Operation “Protective Edge”—brought to life scenes grimly reminiscent of those streaming out of the strip right now:

“I looked and saw three trucks drawn across to block the street; their windows covered in bullet holes and the tyres punctured. There were bodies in there. They [Israeli army] had killed the drivers… I looked out left and right and saw bodies every three or four metres. Every three or four metres a child, a woman, a young boy, a young girl. All dead. We were looking to see if there was anybody moving. But they were all dead. None of the bodies was intact.”

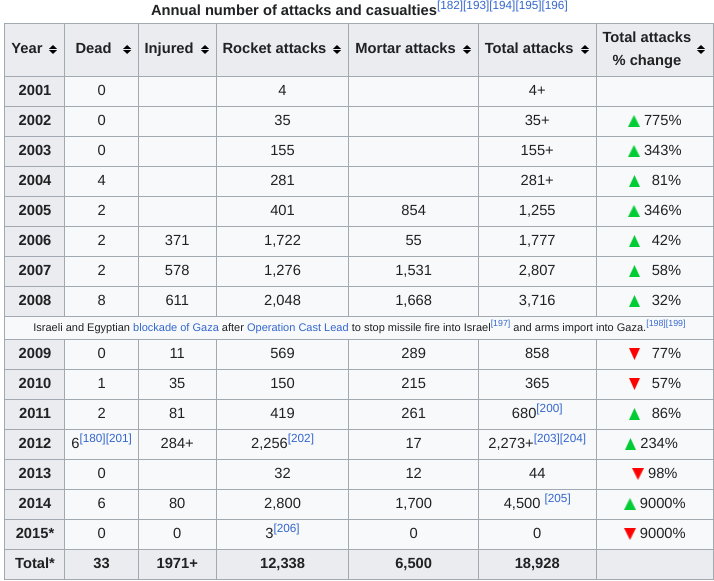

True enough, an unchastened Zionist might rejoin, but what about the barrage of rockets Hamas had been firing at civilian communities in southern Israel during the same timespan? Of course, this point is only germane for our purposes if it can be shown that rocketfire emanating from Gaza had been more lethal (on average) than attacks by Palestinian insurgents in the West Bank during the period concerned. So was it? I will allow the data to speak for themselves:

Figure 1: Israeli casualties as a result of Hamas attacks (table compiled by Wikipedia drawing on data from a variety of sources)

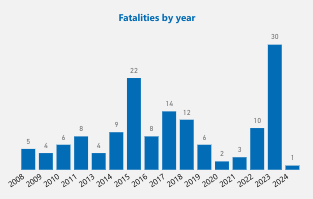

Figure 2: Israeli fatalities in the West Bank, 2008-2024

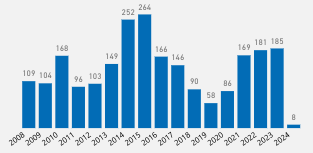

Figure 3: Israeli injuries in the West Bank, 2008-2024

Thus if we limit ourselves to the only period when the two datasets overlap (2008-2015), we find that Israeli fatalities and injuries in the West Bank were either greater (36 > 23) or roughly equal (981 ~ 1102) to their counterparts in southern Israel, respectively. Note that this comparison drastically understates the actual per capita disparity in risk seeing as more than twice as many Israelis inhabit southern Israel as the West Bank.

A more plausible explanation for Israel’s (extremely relative) benignity in the West Bank compared to Gaza is military necessity. Put simply, due to its decades-long overlordship of the former and simultaneous absence (at least until recently) in the latter, the Israeli army has no need to substitute its ground troops in the West Bank with bombs and fighter jets; it can simply deploy its men as needed. Yet such an account reverses the actual ordinality of “need” which informs the IDF (and, indeed, every military)’s risk calculus. As anyone learned in the art of war knows, you can spare your soldiers a great deal of pain by taking their work to the skies. Israel is well aware of this, hence why on the occasions that it has made use of aerial power, it has almost invariably hewed to the principle of maximizing destruction wherever possible as a means to both (a): deny its enemies any potential combat advantage, and (b): thereby minimize the domestic backlash that would ensue from high combatant casualties on its account. Examples of such politicking by other means are legion in Zionist military history. To note just one, consider the IDF’s last major assault on southern Lebanon before its withdrawal from the territory in 2000 (Operation “Grapes of Wrath”). On the eve of this most recent exercise in disciplining its Arab neighbors, Israeli forces issued an ultimatum to civilian communities in southern Lebanon: evacuate to your country’s north without hesitation—or face certain death. Israeli government spokesperson Uri Dromi laid out the rationale for this apparent lapse in martial probity in blunt terms: “We gave the residents advance warning to clear out so as not to get hurt. All those who remain there, do so at their own risk because we assume they're connected with Hizbollah.” Yet more explicit was Israel’s regional proxy force, the South Lebanon Army, which announced via radio:

In light of the continued terrorist actions by Hizballah, the Israeli Army will intensify its activities against the terrorists starting tomorrow, 14 April 1996. Following the warning broadcast by the Voice of the South to the inhabitants of 45 villages, any presence in these villages will be considered a terrorist one, that is, the terrorists and all those with them will be hit. Any civilian who lags behind in the aforementioned villages and towns will do so on his own responsibility and will put his life in danger [emphasis added].

The military value (if not necessity) of such a battlefield epistemology is obvious: by declaring anything and anyone in its path a legitimate target, Israel could deliver a quasi-fatal blow to its adversary without wasting the time or manpower that would have been necessary to ensure a more judicious approach to waging counterinsurgency. Had any such approach been adopted, the IDF would very likely have jeopardized its political capital given the Israeli public’s well-known intolerance for bartering Jewish combatant lives in exchange for the safety of non-Jewish civilians. In a word, destruction pays, particularly so when one of your war objectives is to stanch popular support for a guerrilla army whose forces you’re otherwise incapable of neutralizing. Grapes of Wrath brought this credo to its logical terminus, most infamously when Israeli forces massacred 106 Lebanese civilians taking refuge in a United Nations shelter for the stated purpose of defending a nearby commando unit (if this is beginning to sound familiar, it should).1

Knowing what we do about Israel’s affinity for mass murder as a substitute for combat, then, why does it seem to pull its punches when engaging Palestinian fighters in the West Bank? Perhaps our question would be better answered by working backwards: what exactly differentiates the West Bank from Gaza post-2005 or southern Lebanon that would render it uniquely immune to protracted aerial campaigns of the sort we’ve seen in the latter two? At last the actual key to our riddle presents itself—the West Bank houses too many settlers for it to be bombed. Whereas southern Lebanon and Gaza since 2005 can both be (and have been) laid to ruins without imperiling the security of Israeli Jews, the same very much cannot be said for the other half of occupied Palestine. The reasons for this are both obvious and myriad. For one—and despite extreme levels of residential segregation between the two populations—Israeli settlers and West Bank Palestinians nonetheless “share” numerous vital spaces. The classic example of this profoundly warped coexistence is the ancient Palestinian city of Hebron. Originally carved into two zones of Israeli and Palestinian control during the Oslo Accords, Hebron is often cited as a microcosm of the conflict due to its epitomization of the most abasing features of Israeli rule. Foremost among these is the presence of a slim yet well-endowed minority of Jewish settlers whose superiority under the law is enforced by daily affronts against the indigenous population. At the juncture separating Hebron’s two halves, this regime of humiliation is given a third dimension by the geographic elevation of Israeli settlers over Palestinian residents, the former of whom are frequently wont to rain detritus of all kinds (including actual human shit) on the heads of the latter.

Figure 4: A commercial avenue in Hebron is overlain by metal sheeting to protect Palestinians from rocks and garbage thrown by Israeli settlers.

Now let’s consider the IDF’s approach to defusing Palestinian militancy in Hebron (which, though far from equal in magnitude or moral weight to the everyday violence of the occupation, is nonetheless a real phenomenon). In 2018, it was reported that the Israeli internal security agency Shin Bet had uncovered a sprawling network of Hamas operatives in Hebron who were implicated in various “terrorism activities,” including incitement of anti-settler attacks, recruitment of potential fighters, and transfers of funds and intelligence. Whether these charges had any merit is irrelevant (though they most likely didn’t). What matters to us is that from Israel’s putative standpoint, Palestinians had transformed Hebron into yet another “hornet’s nest” of anti-colonial resistance in Judea. Indeed, judging by its rules of engagement in Gaza and southern Lebanon, the IDF had stumbled upon a prize as good as any other in the form of this (supposed) renegade Hamas cell. And yet between then and now, we were fortunately spared the sight of Israeli warplanes replicating in Hebron tactics which they had previously perfected in Gaza, such as the bombing of markets timed to coincide exactly with the commutes of Palestinian civilians. Why was this? The answer, as I should hope by now, is obvious: Israel couldn’t have done to Hebron what it had been doing to Gaza for years without putting its settlers in harm’s way. This fact is most obvious of all when we consider the aforenoted buffer zone, where any explosive destined for the Palestinians of Hebron would necessarily have had to cut through a layer of settlers before it could reach the former. The very physical geometry of the city thus circumscribed the IDF’s usual arsenal, to the point that otherwise passable modes of urban Palestiniocide became untenable.

Admittedly, Hebron is something of a limiting case; it is after all the only city outside of Israel where Palestinians and Israeli Jews live “side-by-side” (however unequally). All the same, Israeli settlements have snaked their way across every major urban center in the West Bank, effectively shattering the territory into dozens of cantons whose boundaries are constantly in flux. This protean spatial arrangement (a classic feature of settler-colonial frontiers) lends itself to a unique kind of asymmetric warfare in which Israeli mobility assumes the status of a tectonic force, quietly molding the demographic landscape of Palestine while simultaneously loading the spring for periodic bursts of kinetic energy. Since early last year, what we might call the dialectic of ordinary displacement has intensified rapidly, effectuating the sweeping “transfer” (that long sought-after telos of the Zionist dream) of Palestinians from their homeland and the appropriation of the latter by Jews. Crucially, settlers must enjoy more or less total freedom of movement throughout the West Bank in order for this policy to be logistically feasible, including areas populated by Palestinians. The Israeli human rights monitor B’Tselem has documented copious instances of settler banditry targeting Palestinians in exactly these areas, in some cases emptying whole villages of their residents within a matter of days. The following account is paradigmatic in this regard:

On Wednesday, 14 February 2024, four settlers arrived at Wadi ‘Abayat and tried to enter the Sawarkah family tent, while Ibrahim Sawarkah was home with his wife and eight children. Ibrahim Sawarkah (38) blocked their way and demanded they leave. The settlers did leave, but returned about 15 minutes later with clubs and 10 dogs. The family hid inside the tent and called the police, who promised to send soldiers to the scene.

The settlers punctured the tires of the family’s tractor and car and smashed the car’s windows. They entered the tent, pepper sprayed the mother in the face and left. At the same time, a settlement guard arrived at the scene and blocked the way to the family’s home with his car. Soldiers arrived about 20 minutes later and simply let the settlers leave. The soldiers asked Sawarkah what had happened and left after he told them.

The next morning, Thursday, 15 February 2024, soldiers arrived at the family’s home in a military jeep, demanded Ibrahim Sawarkah’s ID card, handcuffed him, blindfolded him and put him in the jeep. The soldiers took him to the Etzion police station, where he was held for several hours and then interrogated by police officers for allegedly having assaulted a settler. The police then released him, and he found out relatives had taken his wife, children and the family’s flock to their home in al-Maniyah, north of Kisan, and had towed the family’s tractor there too.

The family spent the night in al-Maniyah. When Ibrahim Sawarkah went home the next day, he discovered settlers had torched his tent and car. As a result, the family was forced to remain in al-Maniyah.

In at least one sense, then, Israeli parsimony in containing the Palestinians of the West Bank is a strategic necessity: not only is it enabled by the ventures of a trigger-happy settler strike force, it ensures maximally safe conditions on the ground for this strike force by sparing it from the effects of aerial bombardment, whether in the form of direct hits and/or unexploded ordnance (the latter of which has posed an omnipresent hazard to Palestinians in Gaza for years). In this way, Israel can engineer the “facts on the ground” it deems necessary while avoiding the potentially troublesome prospect of these facts being annihilated in the process.

Yet there is another, arguably even more salient incentive for Israel to pare back its homicidal tendencies when operating in the West Bank, and it has everything to do with Malm’s discursus on the political ecology of Zionism. To understand what this is, however, we must first consider the counter-factual:

In Gaza, where it has been going on for decades, destruction [of the environment] has now reached apocalyptic proportions: the people who have not yet died from the bombs live in a wasteland of contaminated soil, undrinkable water, orchards and fields packed into dust, garbage and debris mixed in a hyper-polluted strip of land in which human life is being rendered impossible for the long term. Ecocide here fuse with genocide in a manner never seen before. Bosnia was not a less habitable land after 1995 than before 1992. Rwandan soil and water and air went relatively unscathed through the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Tutsis. But will people ever be able to live again in Gaza? [emphasis mine].

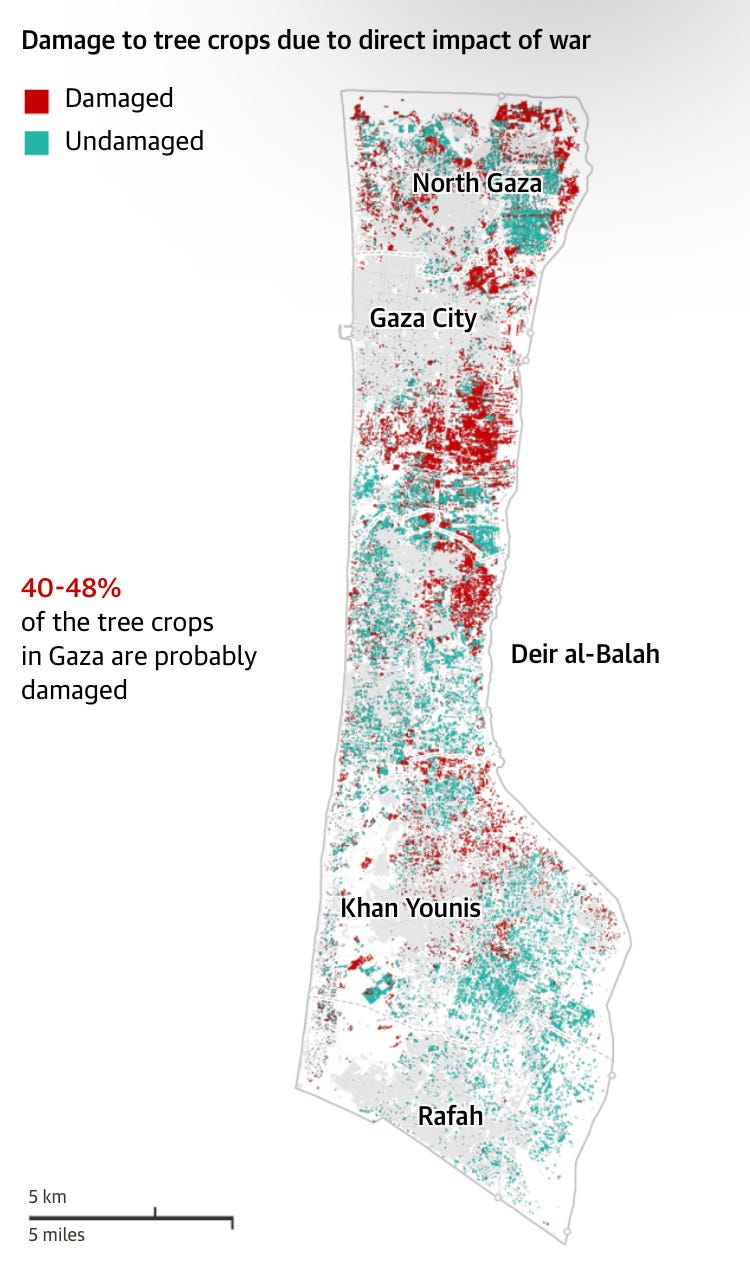

This is a question seriously worth considering, not least because the answer thereto can tell us a great deal about the viability (and thus probability) of Jewish resettlement in Gaza. Malm has already given us several helpful clues in this direction: aquifers polluted beyond repair; topsoil either bulldozed or filled to the brim with heavy metals; epic mountains of waste that only grow by the day. To these I will add only two more points. First of all, Israel’s reign of destruction has not confined itself to the Earth’s crust. On the contrary, for every bomb dropped or tank shell fired, a no less effective blow is dealt to the survivability of Gaza’s air. Though the picture is still blurry, preliminary analyses suggest that concentrations of CO, NOx, and PM2.5 have all increased rapidly, and likely well past the thresholds beyond which human health begins to suffer. Secondly, the sheer intensity of the bombardment thus far may very well induce a new wave of ecological succession in Gaza, though the likelihood that this unfolds in a manner conducive to human flourishing is thin absent concerted intervention. As it happens, we can already gain an appreciation for the sheer magnitude of the challenge ahead: per one recent estimate, almost half of all tree crops in Gaza have been damaged by IDF operations or (what amounts to the same thing) Palestinians foraging for alternative sources of fuel since October 7.

Figure 5: Map/analysis credited to The Guardian

Now consider a hypothetical scenario in which anything close to the balance sheet assembled above was inflicted on the West Bank; the whole raison d’etre of the settlement enterprise (i.e. implanting Jews on Palestinian land) would be obviated virtually overnight. Not only would several of the positive inducements for relocation from Israel to the West Bank (e.g. attractive vistas, rural livelihoods, etc) disappear, but uncountable more negative inducements would emerge in their place. To be sure, Israeli settlers are among the most ideologically diehard of their country’s population, but not even a mandate handed down from Providence himself will save you from the effects of waterborne illness. We can thus state the following as a general principle of Zionist statecraft: whatever you do to Palestine, abstain from ruining its choicest real estate. Conversely, wherever the settler regime has either largely given up on its original aims (Gaza) or never saw fit to pursue them in the first place (southern Lebanon), anything goes, even—and perhaps especially—if that means obliterating the lives of the local indigenes in the process.2

Conclusion

The perversely “discriminatory” nature of the Israeli war machine elaborated herein bears many similarities to the climate crisis’ own in-built mechanisms for maximizing loss of life among the dispossessed. True enough, the latter are mediated by forces several times more abstract than the former: extractivism and debt traps, geography and inter-imperialist rivalry. But at the end of the day, the respective human tolls of both invite just as little contrition from the powers that be. To borrow Malm’s poignant account of last year’s catastrophic flooding in Libya—yet which could apply in equal measure to the bloodletting in Gaza—these victims are no more than “the wretched of the earth, dying as they always do, in the Mediterranean and other graveyards of the world.” The invocation of the graveyard carries a particular ironic resonance in the case of Gaza, where Israeli forces have both uprooted Palestinian cemeteries with abandon and dug up mass graves to conceal evidence of fresh wrongdoing. To this I would like to add a metaphor of my own: here in the United States, a federal program known as the Superfund is responsible for cleaning up areas that have been (for one reason or another) struck by dangerously high concentrations of hazardous waste. Such areas are referred to in popular lingo as “Superfund sites,” and though several have been successfully contained or remediated, many more continue to pose real public health liabilities to local (disproportionately non-white) residents. With this in mind—and granting that the devastation wreaked by Israel dwarfs anything Americans have ever had to endure—we might theorize postwar Gaza as the global Superfund site par excellence: a containment zone for every noxious element known to man, be it life-threatening toxins or subaltern resistance.

As the global buildout of hydrocarbon infrastructure proceeds apace, it should come as no surprise that localized Gazas are beginning to pop up with rising frequency: an indigenous islander community in Panama driven off its land by ballooning sea levels; Fulani herders in West Africa trapped between the dual vise of desertification and state-sponsored ethnic violence; Iraqi fisherman made redundant by marshlands parched for water. Everywhere that the concentrated energy of fossil power has been deployed—whether randomly in the form of heat-trapping gases or more consciously via the destructive might of colonial armies—its results are disturbingly consistent. Perhaps the most stable among these is the basic sense of insecurity that it generates for its targets. Long ago banished from the realm of petty production (and for those cast aside by capital, that of production tout court), these unlucky souls face the same choice which confronted the people of southern Lebanon in 1996 or Gaza right now: flee or die. “Primitive accumulation” hardly begins to capture it. What we are witnessing unfold is nothing short of a generalized assault on the social metabolism of humanity (or, to be more precise, those segments of humanity which have been coded for annihilation). To underscore the sheer exigency of the current moment, allow me to borrow a concept from mathematics: if the metropoles of the world are where value goes to be renewed, the Gazas of the world are where it goes to die.

Conversely, if Gaza can be said to mirror the mass death currently being wrought by rising temperatures across the Third World, then Israel’s security villages in the West Bank represent the compulsion of our elites to retreat into their own walled-off oases in the face of certain ecological ruin. These might be literal, as with the notorious “doomsday” bunkers currently being erected by the uber wealthy to ensure that their fortunes outlive the rest of us (and even themselves). More often, however, they assume the spirit of metaphor: a mushrooming global network of borders and watchtowers designed to enforce the captivity of non-white labor and thereby prepare it for its march into the planetary death chamber. A prelude of the catastrophe (one might say Nakba) to come was provided to us a few years ago by the World Meteorological Organization. By its accounting, of two million deaths worldwide attributable to “weather, climate, and water hazards” from 1970 to 2019, over 91% took place in the Global South. Considering that large swathes of the world’s exploited masses have already been locked out of refuge in the countries best capable of accommodating them, there is little reason to believe this proportion will fall. What’s more—and true to its genesis as an arm of empire—Israel has played a vital role in laying the scaffolding for this global cordon sanitaire. In addition to warehousing thousands of East African asylum seekers in camps along the Naqab desert, the entity has also thrown its weight behind efforts to arrest rogue population flows to the US and Europe. No doubt the hecatombs in Gaza will supply the grist for many a future police operation against the global poor, as indeed they already have at a Singaporean weapons expo last month. In the meantime, settler life continues as per usual, unmoored by the horrors carried out in its name while simultaneously grateful for the perks it derives therefrom. At the end of the day, its investments are the ones that count, and to let them be destroyed would be just as irrational as a rig operator or gas merchant ceding their own assets to the agitation of the rabble.

Against a global counteroffensive of such titanic proportions, resistance is not merely one prudent option among many—it’s a matter of life or death. Fortunately for us, in addition to serving as a laboratory for the most Caligulan tools in the arsenal of bourgeois civilization today, Palestine also happens to be home to one of the most important revolutionary traditions of our age. Recent calls by student protesters around the world to “globalize the Intifada” are living proof of this fact, and though I wholeheartedly affirm their struggle, I would like to add my own two cents about what this demand actually means. And what it means, quite simply, is to eviscerate the ultimatum currently being imposed on us by the Israels and the Americas and the Australias (AND WHOEVER ELSE YOU’D LIKE) of the world. To stand firmly in place despite anything and everything thrown our way, and to sabotage the efforts of those who would gladly watch us pass away into oblivion. In this, we would do well to take a page from the Palestinians, whose own century-spanning trek for liberation—from the first Arab village to be evicted at the behest of settlers to the millions presently threatened with subtraction from their homeland entirely—begins and ends with the very idea of steadfastness, or sumud. To follow in their path is nothing short of a cosmic injunction, one whose necessity is confirmed daily by the terminal crisis—and parallel metastasis—gnawing at capitalist development today. Nor can the biosphere afford any further delay; its fate is only too bound up with those who would be most devastated by its ruination. Thus for its sake and the rest of ours’, let us declare without an ounce of hesitation or apology:

FROM THE RIVER TO THE SEA, PALESTINE WILL BE FREE!

1 - For further exploration of this matter, see my friend maikas’ recent article “IOF,” in which he presents a piercing psychoanalytic account of Israeli counterinsurgency.

2 - So to answer posed by this essay’s title in a sentence: you don’t bomb land you’re trying to actively colonize.

🔻 2025 Humble_Humboldt. All rights waived for the third world. No rights granted to the imperial core or its collaborators.